DC84: Chapter 3: Fields and Awareness

Why change only happens when we work with what’s already in the room

This chapter is for those of us who always knew something was missing.

For those of us who sat through the framework wars and felt, even then, that they had missed the point entirely.

For those who read the first SAFe rollout deck or attended the first scaling workshop and sensed that, whatever problem this was solving, it wasn’t the one we were actually facing.

For those who knew, long before the evidence piled up, that layering new structures, roles, and ceremonies onto old assumptions could never produce real change.

We didn’t always have the language for it.

But we felt it.

We knew there was something operating behind the visible system. Something that tied behaviour to the status quo, that pulled even the best-intentioned leaders back into the same decisions, the same patterns, the same failures, despite decades of research telling us about flow, lean thinking, team dynamics, psychological safety, automation, and learning.

Managers weren’t stupid although stubborn on occasion.

Teams weren’t resistant although disinterested more than once.

The information wasn’t missing at least if you could be bothered to learn about flow etc.

Something else was at work.

In the previous chapters, we explored how paradigm shifts unfold and why organisational change keeps stalling when it is attempted from an outdated worldview. We saw how industrial-age thinking survived inside modern language, and how agility, systems thinking, and mindset work improved parts of the picture without ever shifting the whole.

There is a reason for that.

Every organisation operates inside an invisible context, a system behind the system, that shapes what feels possible, what feels risky, and what never quite makes it into the conversation. You can’t see it on an org chart, but you can feel it the moment you walk into a room. You know who really decides. You know what not to say. You know when a conversation is real and when it’s theatre.

This is the field.

A field is what a paradigm feels like when it is lived. Regardless of your belief system.

Most organisational change fails not because the strategy was wrong.

Not because the structure was poorly designed.

Not because people were resistant or incompetent.

It fails because the field never changed.

Those of us who resonated with The Matrix on a deeper level recognised this instinctively. We knew there was something beneath the surface, something shaping behaviour without ever being named. A wiring under the boards. A gravity holding everything in place.

This chapter gives us language for that missing layer. Not a new framework, not another methodology to roll out, but a way of seeing what has always been there. It introduces fields and awareness as the next level of organisational change, the layer beneath systems, culture, and behaviour. I explain why real, lasting change only becomes possible when we learn to work with what we are already standing inside.

What is a field?

A field is the invisible relational context that shapes behaviour long before anyone consciously decides how to act.

It is not written down.

It is rarely acknowledged.

And yet it quietly determines almost everything.

A field is made up of emotional tone, shared assumptions, power dynamics, and the unwritten rules of permission and risk. It governs what is rewarded and what is punished, what can be said safely and what must remain unspoken, and who really makes decisions when it matters.

You will never find it on an organisational chart.

But you can feel it immediately.

Walk into a meeting and, within seconds, you know whether honesty is welcome or dangerous. You sense whether disagreement will be explored or quietly remembered. You can tell whether the conversation is real, or whether decisions have already been made elsewhere and this is simply theatre.

That immediate, pre-verbal knowing is field awareness.

It explains why two organisations can share the same structure, processes, roles, incentives, and even values and yet behave in completely different ways under pressure. The difference is not the design. It is the field they operate within.

Sensing the field: a personal example

I learned to trust this kind of knowing the hard way. I am hoping that this chapter and book helps your learn it the easy way.

Several years ago, I was invited to help the a large European Bank prepare a change plan to be presented to senior leadership. On paper, it was an exceptional opportunity. The bank does genuinely important work, supporting development across regions that desperately need it. I was excited by the mission and honoured by the invitation.

I went to their headquarters for what was framed as a mutual exploration: half a day of conversations to understand the challenge, assess fit, and decide whether we wanted to work together.

The formal meetings went well. The people I was scheduled to see were thoughtful, articulate, and clearly committed to doing the right thing. The story I was being told was coherent and compelling: a desire to evolve, to modernise, to become more adaptive and effective.

And then we went for lunch.

Sitting in the canteen with people who were not on my official list. These are staff who had no reason to impress me or sell a narrative, they didn’t even know why I was there. I encountered a very different reality. The energy in the room shifted. Conversations dropped in volume when certain people walked past. There was a visible tightening in bodies, a carefulness in language, a subtle but unmistakable sense of caution.

This did not feel like a safe place to work.

Especially not as a contractor.

What struck me most was the distance between the external mission and the internal lived experience. The organisation’s public ethos of development, empowerment, and progress, was not mirrored in the everyday field of interactions inside the building. The people doing the work were far removed from the front line of impact, and the emotional climate reflected that separation.

Nothing overtly “bad” happened.

No one said anything explicitly alarming.

And yet the field told a very clear story.

As I continued the conversations and asked to speak with some of the managers who would be present at the eventual presentation, it became increasingly obvious that this was not an organisation ready for the kind of change they were asking for, and certainly not ready for me!

To succeed, I would have had to compromise who I was, how I worked, and the conditions I knew were necessary for real change. I would have needed protections, access, and authority that I suspected they could not, or would not, provide.

So I made a deliberate choice.

I named an essential requirement for the work that I knew would be a deal-breaker. Not as a provocation, but as a boundary. As expected, they declined. We did not work together.

This was not a failure.

It was a successful reading of the field.

Trying to operate differently inside that field would not have changed the organisation. It would have changed me. And not in ways I was willing to accept.

Why this matters

That experience clarified something fundamental.

Change does not fail because people lack skill, intelligence, or good intent. It fails when the field of awareness and resulting action inside an organisation is incompatible with the change being asked for.

No amount of frameworks, roadmaps, or executive sponsorship can compensate for a field where fear, status protection, and silence dominate. In such fields, even the best methodologies are absorbed and neutralised.

This is why experienced change practitioners learn to trust what they sense, not just what they are told. The field is always more honest than the narrative.

Fields in theory and practice

What I sensed at the bank was not intuition in the mystical sense. It aligns closely with how fields have been described across multiple disciplines.

Kurt Lewin, one of the founders of organisational psychology, defined behaviour as a function of the person and the field , recognising that context shapes action as much as individual capability.

Gestalt practitioners speak of “what is present in the room”, working with the lived, relational reality rather than abstract plans.

Systems coaches describe “the system in the room”, acknowledging that dynamics between people are more influential than individual intent.

More recently, work on WE space and coherence has made this explicit: the field is the shared relational space we are all participating in, whether we acknowledge it or not. When that space is coherent, trust, learning, and adaptation emerge naturally. When it is incoherent, control, politics, and stagnation follow.

Different language. Same underlying truth.

A field is the system behind the system.

The wiring under the boards.

The context that decides what is actually possible.

Why field awareness changes everything

Once you learn to notice fields, you stop taking organisational behaviour personally. You stop blaming individuals for systemic patterns. You stop trying to force change where the conditions cannot yet support it.

And most importantly, you gain the ability to choose.

You can decide whether a field is one you can work within, one you can help shift, or one you must step away from, without self-betrayal.

This is the level of awareness required for real change. Not louder leadership with force, or even more servant leadership. Certainly not better frameworks. But the ability to see, name, and work with what is already shaping behaviour before anyone speaks. It feels mystical, but only because any science seems that way to those who cannot see how it works.

Where does this idea come from?

The idea of fields is not new, fringe, or spiritual.

It appears wherever mechanistic explanations stop being sufficient. Whenever people realise that breaking things into parts no longer explains how behaviour actually emerges, the language of fields begins to surface.

I didn’t encounter this idea first in organisations.

I encountered it much earlier.

Physics: where the idea first made sense

I went to university to study physics. At the time, I had no idea how much that choice would shape the way I later understood organisations, relationships, and change.

Physics teaches you very quickly that objects do not act in isolation. What matters is not just the thing itself, but the field it is embedded in. Gravity is not something an object possesses. It is a relational force that arises between bodies. Magnetism is not a property of metal; it is a field that shapes attraction, repulsion, and alignment.

Each field has a quality, a direction, and an intensity.

While studying these ideas formally, I found myself applying them informally to everyday life. I began to notice how people, like planets or magnets, create fields around themselves. Some people generate ease, clarity, and movement. Others generate caution, tension, or inertia. The same person can create very different fields in different contexts.

Once you start to see this, it becomes obvious why some interactions flow and others block, even when the same people, skills, and intentions are present. What’s different is not the components. It’s the field.

That early insight stayed with me. Long before I had language for organisational change, I had an intuition that how things relate matters more than what things are.

Psychology and social psychology: fields inside relationships

Later, my attention turned more explicitly toward human dynamics. I trained as a therapist, specialising in couples’ relationships, because I wanted to understand how trauma shows up in everyday interactions, and, crucially, how it can be healed.

Couples therapy is fieldwork in its purest form.

Very often, the issue is not what either person is doing in isolation. It’s the relational field they are co-creating: the emotional tone, the unspoken fears, the historical injuries that shape how every word lands. Change happens not when one person “improves”, but when the field between them shifts.

This mirrors exactly what Kurt Lewin articulated decades earlier when he wrote that behaviour is a function of the person and the field. He used field theory to explain resistance to change, leadership dynamics, and group behaviour, long before organisations tried to industrialise change management.

Later work in social psychology , social identity, group norms, emotional contagion, psychological safety , all describe local social fields. They simply approach them from different angles.

I began to apply this relational lens directly to organisations. Something as simple as changing who is present in a meeting can radically alter what becomes possible. For example, extending retrospectives beyond a single team to include the wider product group often shifts identity from “my team” to “our product”. Problems that previously felt interpersonal suddenly become systemic. Flow improves. Delivery improves. And all of this can happen without ever explicitly addressing delivery at all.

The field changes, and behaviour follows.

Systems thinking: necessary, but incomplete

Systems thinking was a major breakthrough in organisational change. The work of Senge, Meadows, Capra and others helped us see feedback loops, emergence, and interdependence. It moved us beyond linear cause-and-effect thinking and gave us better maps of complexity.

But systems thinking often remains cognitive.

We draw diagrams. We model flows. We analyse leverage points. All of this is valuable and still insufficient under pressure.

What systems thinking tends to leave out is the felt dimension: fear, trust, shame, courage, permission. The human experience of being inside the system.

Fields explain why a beautifully designed system behaves very differently when people feel unsafe, threatened, or watched. They explain why rational incentives fail, why learning stops, and why control increases just when adaptability is needed most.

Fields don’t replace systems thinking.

They complete it.

Side note: In the Action Logics system, I believe this is the piece that moves us from Independent to Transformational.

Organisational development and coaching: implicit fieldwork

As I moved deeper into organisational change, I noticed something interesting. Many of the most effective practitioners were already working with fields , even if they didn’t call them that.

Gestalt OD speaks about “what is present in the room”.

Systems coaching refers to “the system in the room”.

Process work explores rank, power, and the edges of awareness.

Team coaching focuses on relationships rather than individuals.

Different disciplines. Different language. Same phenomenon.

Stop fixing people.

Start working with the relational context they are embedded in.

This is why coaching fails when it focuses purely on individual behaviour. You can help someone become more reflective, more courageous, more skilled , and then watch those qualities evaporate the moment they re-enter a hostile field.

Leadership and collective sensemaking: revealing the field to itself

The most profound confirmation of field theory in my work came through large-scale sensemaking interventions.

In several organisations, including banks, I facilitated system-level and team-level work where different parts of the organisation mapped their lived experiences onto a shared visual space. Teams, roles, functions, and layers of hierarchy all contributed their perspective to the same board.

What emerged was extraordinary. For the first time, the organisation could see itself.

Patterns that had been invisible within siloed conversations became obvious when placed side by side. Tensions between strategy and delivery, between leadership intent and lived reality, surfaced without accusation. People recognised themselves in each other’s stories.

The field shifted.

In one case, this shift was so significant that the organisation moved toward product thinking and product-aligned teams without any formal training, frameworks, or agile coaches. There was no rollout. No mandate. Just reorganisation.

By revealing the field to itself, outside the usual lines of communication, the organisation reorganised its own thinking.

Meaning and Identity changed and then Action followed.

This is exactly what Karl Weick described as collective sensemaking, what Heifetz meant by holding the space where the work can be done, and what David Bohm explored through dialogue as a field of shared meaning.

None of it works without a concept of field.

WE space and coherence: making fieldwork explicit

More recently, work on WE space and cohering has made this way of working explicit and teachable.

The field is the invisible relational context.

The WE space is the group’s awareness of that context.

Cohering is the deliberate practice of restoring alignment, trust, and shared meaning.

This is fieldwork brought into the foreground. Not as theory, but as a discipline.

A pattern across disciplines

Looking back, a clear pattern emerges.

Physics.

Psychology.

Systems thinking.

Organisational development.

Leadership.

Sensemaking.

Whenever reality becomes too complex for linear control, attention shifts from objects to relationships, from parts to patterns, from structures to fields.

Organisations are no different.

The field is not a metaphor. It is the system behind the system.

And learning to work with it is the next level of organisational change.

What changes when we work with fields?

When we include fields in our way of working, something fundamental shifts almost immediately. Not because people behave better, but because we start relating to what happens differently.

The organisation does not suddenly become easier.

But it becomes more intelligible.

Patterns that once felt frustrating or personal begin to reveal themselves as information. The system starts to speak, and we learn how to listen.

Resistance becomes information

One of the first things people notice when working with me is a certain calm and confidence in the face of resistance, conflict, or tension. I’m often asked where that comes from.

The answer is simple: I don’t experience what arises as about me.

When resistance shows up, I’m not threatened by it or attached to the outcome. I’m curious. Whatever appears, defensiveness, anger, withdrawal, challenge is coming from the field of that system. It is the system responding to itself. Even when something is directed at me personally, it exists only in that field.

Fear, loss of status, broken trust, misaligned incentives, unspoken grief, these are not obstacles to change. They are the data of change.

Once you understand this and absorb this into your being, the urge to push harder disappears. You stop trying to override resistance and start using it to show the system something about itself. In doing so, people often feel seen for the first time. And when that happens, the field begins to soften.

We all belong to many fields. The field I identify most with is the flowing field of life. Life exists all around us, and is a larger field of experience than the smaller field of the organisational field of getting things done. This gives me an enormous sense of identity beyond that of human endeavours. I draw confidence from this and a huge sense of certainty.

This stance creates a strange paradox: the less personally invested you are in being right, the more influence you tend to have. Because you are no longer fighting the field, you are working with it.

Emotion becomes data

In field-based work, emotions are not something to be managed away. They are actively welcomed.

Emotions are a language in their own right. They are a form of embodied intelligence that often sees what the cognitive mind cannot, or does not want to. Long before people can articulate what is wrong, their bodies already know.

Exhaustion, cynicism, silence, heroic over-functioning; these are not individual weaknesses. They are signals from the field about overload, misalignment, or unresolved tension.

The problem in most organisations is not that emotions are present, but that we lack a shared language for working with them. Emotional literacy in corporate environments is typically underdeveloped, which means vast amounts of information are ignored or suppressed.

When we learn to name emotional tone without drama or blame, something remarkable happens. Fear of emotion gives way to curiosity. Avoidance gives way to insight. What once felt dangerous becomes useful.

This is as true in organisations as it is in intimate relationships. Emotions, when acknowledged and interpreted well, become one of the most powerful drivers of transformation available to us.

Power becomes visible

Working with fields also changes how we understand power.

Power is not just hierarchy or authority. It hides in status, expertise, access to information, relationships, charisma, moral positioning, and even apparently altruistic behaviour. It shows up in who sets the narrative, who frames the problem, and whose version of reality becomes dominant.

Power, at its core, is the ability to shape meaning and decision-making.

When we develop field awareness, these dynamics become easier to see. Both in the system and in ourselves. We begin to notice how we seek influence, how we protect our position, how we try to be heard, accepted, or safe.

This can be uncomfortable. And it is also liberating.

Because once power is visible, it is no longer unconscious. We can work with it rather than pretending it isn’t there. We can stop moralising and start understanding. And we can choose to operate from a deeper source of influence than hierarchy alone.

We can choose whether to support that power or ignore it and understand the consequences for doing so. This is power in its own right.

Field awareness allows us to transcend formal structures and draw power from the only place it ultimately comes from: the shared field of intelligence we all participate in. The power of life or universal consciousness. Power is never owned. It is lent. And learning to align with the field offers a far better return than clinging to positional authority.

Change stops being performative

Perhaps the most striking shift is this: change stops being something we perform.

When people lack field awareness, they compensate with activity. More communication. More alignment sessions. More governance. More enforcement. More theatre.

But when the field shifts, behaviour follows naturally.

People don’t need to be convinced. They don’t need to be coerced. They don’t need to be managed into compliance. They already know what to do because the context has changed.

Those who can sense and articulate the forces at play in a field often appear almost supernatural to others. As if they can “see behind the curtain”.

In reality, nothing mystical is happening. It is simply deep noticing, combined with the courage and skill to name what is sensed in a way the system can hear.

When this is offered as a gift, not as a judgement, coherence emerges. Alignment follows. And very often, that alone is enough to unlock movement, learning, and meaningful delivery without introducing a single new framework.

The deeper shift

Working with fields moves us from force to coherence.

From fear to curiosity.

From control to participation.

And definately from ignorance to courage.

It allows us to stop fighting reality and start learning from it.

And once that happens, change stops being something we do to organisations, and becomes something that emerges through them.

What disrupts our ability to read fields?

Our ability to read fields is not fragile; it is innate. Humans evolved to sense social context, power, belonging, and danger long before we learned to analyse or plan. We are exquisitely sensitive to what is happening between us.

When that sensitivity collapses, it is not because people are incapable or unskilled.

It is because the field has become overwhelming, fragmented, or unsafe.

Across organisations, the same disruptions appear again and again. They are emotional in nature, systemic in origin, and predictable in their effects. When left unacknowledged, they distort perception. When recognised, they become some of the richest sources of information available to us.

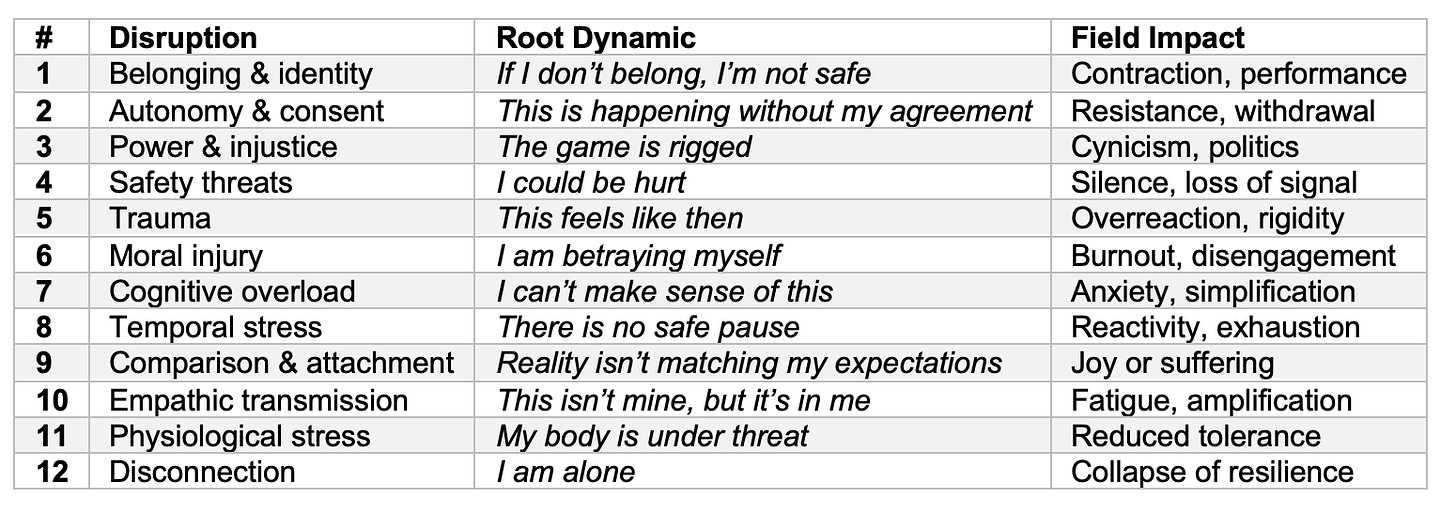

The most disruptions to field awareness that I have worked with and identified as common causes are:

1. Threats to belonging and identity

2. Violations of autonomy, agency, and consent

3. Power asymmetry and injustice

4. Threats to physical, emotional, or psychological safety

5. Unprocessed personal and collective trauma

6. Fractures in meaning, purpose, and moral coherence

7. Cognitive and sense-making overload

8. Temporal stress and loss of rhythm

9. Comparison, attachment, and unmet expectation

10. Empathic and emotional field transmission

11. Physiological and neurochemical stress

12. Disconnection from a larger context or purpose

Each of these disrupts our ability to sense the field in a specific way. None are personal failings. All are signals.

1. Threats to belonging and identity

The fastest way to collapse field awareness is to threaten belonging.

Humans are social survival systems. Long before we worried about performance or delivery, our nervous systems learned to scan for signs of inclusion or exclusion. Being seen, heard, and taken seriously is not a “nice to have”; it is a prerequisite for safety.

When people feel overlooked, misunderstood, misrepresented, or quietly sidelined, something fundamental shifts. Attention turns inward. Energy that could have been used to sense the wider system is redirected toward protecting identity. People begin to manage how they appear rather than attune to what is happening.

Loss of role, status, or relevance has a similar effect. Even subtle signals, for example, a meeting you are no longer invited to, a decision made without you, a joke that lands a little too close to home, can trigger a deep contraction.

Shame, especially when exposure happens without consent, is particularly corrosive. It collapses the field into self-consciousness.

In these conditions, people do not stop caring about the organisation. They stop being able to read it clearly. The field narrows to the question: Do I still belong here? Until that question is resolved, awareness remains compromised.

2. Autonomy, agency, and consent violations

Field awareness also collapses when agency is removed.

This happens whenever people experience that something is being done to them rather than with them. Needs are ignored. Boundaries are crossed. Choices are constrained or presented as illusions. Urgency is imposed without explanation. Compliance is framed as alignment.

Surveillance accelerates this effect. When people know they are being watched, measured, or scored without meaningful consent, attention shifts away from sensing the field and toward managing exposure. Behaviour may become more compliant, but awareness diminishes.

The nervous system’s response is predictable. Resistance emerges, sometimes openly, sometimes quietly. People withdraw, comply mechanically, or find subtle ways to protect themselves. None of this is rebellion. It is a response to lost agency.

When consent is bypassed, the field becomes brittle. People stop offering real information and start offering what they believe is required. The system loses access to its own intelligence.

3. Power asymmetry and injustice

Power distorts fields when nobody names it.

When decisions are made elsewhere without explanation, when punishment arrives without voice or appeal, when standards shift depending on who you are, people quickly learn that reality is not shared equally. Speaking truth upward becomes risky. Responsibility exists without authority. Double binds multiply.

I see this happening frequently with Product Managers who are supposed to guide the product to success but have no authority to make decisions.

The felt experience is not subtle: the game is rigged.

In such environments, people adapt. They become political not because they enjoy it, but because survival demands it. Energy that could have gone into sensing patterns or improving outcomes is diverted into managing relationships, narratives, and risk.

The field grows opaque. Leaders receive filtered information. The organisation appears calmer and more aligned than it really is. Over time, cynicism replaces engagement and intelligence drains quietly out of the system.

4. Threats to safety

Safety; physical, emotional, and psychological, is the precondition for perception.

When people fear humiliation, blame, or reputational damage, awareness narrows immediately. When jobs, visas, income, or standing feel precarious, the nervous system prioritises protection over curiosity.

Often it is not the current threat that matters most but remembered punishment.

Organisations have long memories. A single public shaming, a career-ending mistake, or an inconsistent response to failure can shape behaviour for years.

In unsafe fields, silence becomes rational. Harmony becomes performative. Meetings sound aligned while reality goes underground. What is said no longer reflects what is known.

The field may appear stable, but it is starving itself of signal.

Some people call these ghosts in the system.

5. Unprocessed trauma (individual and collective)

Trauma disrupts field awareness by collapsing time.

When trauma is present, personal, organisational, or collective, the current events are unconsciously interpreted through the lens of past harm. A restructuring echoes an earlier betrayal. A leadership change reactivates memories of collapse. A missed commitment revives old distrust.

This is why reactions often feel disproportionate. They are not fully about what is happening now. They are about what happened then.

Trauma fragments the field. Some people become hypervigilant. Others withdraw. Some push for control; others disengage entirely. Until what happened is acknowledged and integrated, the system cannot stabilise.

Rational explanations do little here. The field needs recognition before it can regain coherence.

I have studied trauma in great depth and even became a trauma therapist. Trauma requires specialist help to reintegrate the wounded part back into the system. This cannot be ignored.

6. Meaning, purpose, and moral injury

Some of the deepest field disruptions are almost invisible.

Moral injury occurs when people are asked to act against their values, to do work that harms others, or to remain silent about things they know are wrong. It also arises through endless work that feels empty, extractive, or disconnected from real impact.

The gap between stated values and lived reality is particularly damaging. When organisations speak one language and reward another, people experience an internal fracture. The question becomes: Who do I have to be to survive here?

This was the primary feeling in the bank I discussed earlier.

When caring becomes costly, people protect themselves by numbing out. Burnout, quiet quitting, and anger are not signs of laziness. They are signs that meaning has collapsed.

In such fields, awareness dims not because people lack insight, but because staying awake hurts too much.

7. Cognitive and sense-making overload

Modern organisations routinely overwhelm the mind.

Information arrives faster than it can be processed. Priorities conflict. Narratives shift weekly. Context switches are constant. Metrics multiply without meaning. There is no time to integrate or reflect.

The result is not confusion so much as saturation. People cannot form a coherent picture of what is happening or what matters most. When sensemaking collapses, the nervous system seeks certainty.

Simplistic explanations flourish. Control impulses rise. Blame replaces curiosity. The field loses nuance and depth, and with it the capacity to adapt intelligently.

A flooded system cannot read a subtle field.

8. Temporal stress and loss of rhythm

Time itself shapes awareness.

Chronic urgency erodes field perception more effectively than almost anything else. When everything is critical, nothing can be properly sensed. When there are no pauses, there is no awareness.

Perpetual change without integration leaves the system permanently unfinished. Artificial deadlines divorced from reality create constant pressure without progress. Endings disappear; only starts remain.

The body learns quickly: there is no safe pause.

Without rhythm, reaction replaces reflection. Presence collapses. The field becomes shallow and brittle, incapable of holding complexity.

9. Comparison, attachment, and expectation

Comparison quietly distorts perception.

People compare roles, recognition, progression, and reward. Scarcity thinking takes hold. Attachment forms around outcomes, identity, or status. Expectations, often unspoken, about fairness or appreciation go unmet.

The tension is internal: reality isn’t matching my inner contract.

This is where joy and suffering diverge. When attachment is high, and reality diverges, disappointment and resentment grow. When attachment loosens, curiosity and creativity return.

Fields shaped by comparison tend toward competition rather than collaboration, even when collaboration is explicitly encouraged.

This is often summarised by the elephant in the room, and most importantly, it is what creates most of the work for consultants. I don’t think I have ever been asked to fix something that was actually the real thing that needed fixing. If it were, they could have done that without me. The actual problems have caused a disruption in the field that is causing a lack of ability to see clearly, and that means they can’t solve the underlying issues.

10. Empathic and field transmission

Fields transmit emotion whether we acknowledge it or not.

Leaders’ nervous systems set tone. Witnessing harm or injustice leaves residue. Unspoken grief, anger, or fear circulates beneath the surface. Media saturation amplifies threat narratives and normalises anxiety.

Often people are carrying emotions that are not strictly theirs. The experience is subtle but familiar: this isn’t mine, but it’s in me.

Without containment, empathy becomes exhaustion. Compassion turns into fatigue. What could have guided the system instead overwhelms it.

There has been a lot of studies done now on empathy and our neurological ability to feel what others feel. It is a powerful phenomenon and one in which we rely on to build a full picture of the field. However, when we are unprepared, ungrounded, or overwhelmed, it can stop us from seeing things clearly.

11. Physiological and neurochemical stress

Field awareness is embodied.

Hunger, sleep deprivation, illness, chronic pain, hormonal shifts, and stress chemistry dominance all reduce tolerance and distort interpretation. Neurodivergent sensory overload adds further strain.

When the body is under threat, perception narrows. This is not weakness. It is biology.

Organisations routinely ignore this layer, designing work as if people were machines. The result is predictable: diminished awareness and degraded decision-making.

12. Disconnection from a larger context

Finally, field blindness deepens when people feel alone.

When work becomes disconnected from purpose beyond self, when identity fragments into “work self” and “real self”, when community thins and meaning evaporates, resilience collapses.

Reduction of the human being to role or function drains vitality. Disconnection from nature, cycles, or something larger than the immediate task leaves people brittle and isolated.

The underlying feeling is simple and devastating: I am alone in this.

In such fields, hope drains away. Awareness dims. Everything feels heavier than it needs to be.

Summary: the 12 sources of field disruption

The thread that runs through all twelve

None of these are personal failures.

They are conditions.

When emotions are acknowledged and integrated, they sharpen field awareness.

When they overwhelm or are suppressed, they distort it.

Field blindness is not a lack of intelligence or intent.

It is a signal that the conditions for perception have broken down.

Restore those conditions and the field becomes readable again.

And when the field becomes readable, change becomes possible.

What can we do about it?

Restoring field awareness is not about techniques, tools, or interventions.

It is about the quality of attention we bring to what is already happening.

Before we talk about repairing disruption, it’s worth remembering something simple and easily forgotten: when none of the conditions we described earlier are overwhelming the system, human beings are naturally adept at reading fields. We do this all the time, often without realising it.

Think of sitting in a café or restaurant, watching people interact. Without effort, you sense relationships, tensions, affections, hierarchies, and moods. You don’t analyse, you notice and appreciate. You hold the unfolding scene with quiet curiosity and reverence.

This is field awareness in its most natural state.

At its heart, reading fields requires a stance of appreciation for whatever is unfolding, rather than a need to control or correct it. It asks us to hold others, and ourselves, in something close to unconditional positive regard. Not approval. Not agreement. But respect for the intelligence of what is already present.

This quality of attention has been described, cultivated, and protected across cultures and traditions for thousands of years.

The inner conditions for field awareness

Across disciplines, the same insight appears again and again: the state of the observer matters.

Nancy Kline speaks of the “time to think”. The radical idea that when people are given space, attention, and freedom from interruption, their intelligence emerges naturally. Not through pressure, but through permission.

Meditative traditions, particularly those that developed in India, place stillness of mind at the centre of perception. When mental noise settles, patterns that were always present become visible, the awareness widens and the field speaks more clearly.

Contemplative practices across Christianity, Sufism, Buddhism, and Taoism all converge on a similar truth: when the self steps back, reality steps forward.

Even modern neuroscience echoes this. When the brain is not dominated by threat, urgency, or self-referential rumination, it becomes better at detecting patterns, relationships, and meaning.

It also turns out that women are neurologically wired to be better at this than men.

Throughout history, many cultures have also used altered states, including psychedelics, as sacred tools to perceive patterns that ordinary consciousness filters out. From indigenous shamanic traditions, to the mystery schools of ancient Egypt, to early religious rites, these practices were not about escape, but about seeing more of what is already there. They were held with reverence, ritual, and responsibility, precisely because of their power to dissolve habitual boundaries and reveal deeper coherence.

Whether through meditation, dialogue, ritual, or altered states, the underlying shift is the same:

Quiet the noise that keeps us separate and attune to the larger pattern unfolding through us.

Field awareness is not mystical, but it is deeply relational and it requires humility.

Reading fields well

When field awareness is strong, a few things become possible.

We sense emotional weather without needing it explained.

We notice what is being avoided as clearly as what is being discussed.

We feel where energy is flowing and where it is stuck.

We can tell which truths are waiting for permission.

Crucially, we do this without judgement.

This is why experienced field practitioners often appear calm in the midst of intensity. They are not detached. They are present without being reactive. They understand that whatever is arising is information and not an accusation.

From this place, three practices emerge naturally.

Sensing

We attend to what is happening beneath the words. Emotional tone. Body language. Silence. Pace. What feels alive. What feels constrained.

Naming

We articulate what is present gently and without blame:

“There’s a lot of caution in the room.”

“We seem aligned on purpose, but split on risk.”

“Something feels unspoken here.”

Naming does not force change. It stabilises perception. It allows the field to see itself.

Holding

We create containers where truth can emerge safely: clear purpose, time boundaries, explicit agreements, and visible protection for honesty. This is not just a facilitation technique, it is leadership in complex systems.

Restoring field awareness in the face of disruption

From this foundation, we can now return to the twelve disruptions, not to fix them mechanically, but to restore the conditions they undermine.

When belonging and identity are threatened, we restore visibility and inclusion. We ensure people are seen, heard, and accurately represented. We reduce shame by replacing exposure with consent.

When autonomy and consent are violated, we restore choice. We clarify what is negotiable and what is not. Even constrained choice is still choice when it is named honestly.

When power is asymmetric or unjust, we restore transparency. We make decision pathways visible, match responsibility with authority, and create safe channels for upward truth.

When safety is compromised, we restore predictability. We make consequences explicit, intervene quickly in shaming or ridicule, and replace blame with learning.

When trauma distorts the field, we restore acknowledgement and pacing. We name what happened, allow grief and anger to be legitimate, and slow the system enough for integration.

When meaning fractures and moral injury appears, we restore coherence. We surface value conflicts, reduce hypocrisy, and reconnect work to real human impact.

When cognitive overload overwhelms sensemaking, we restore simplicity and narrative. We reduce inputs, prioritise ruthlessly, and create shared understanding rather than more dashboards.

When time becomes hostile, we restore rhythm. We end things properly, protect pauses, and remove false urgency.

When comparison and attachment distort perception, we restore orientation. We surface expectations, loosen attachment to identity and outcome, and re-anchor in contribution rather than status.

When empathic transmission overwhelms, we restore differentiation. We help people distinguish what is theirs to carry and what is not, and we share emotional load consciously.

When the body is under threat, we restore care. We design work for human biology, not machines, and remove moral judgement from physical limits.

When people feel disconnected from something larger, we restore meaning and belonging. We reconnect individuals to community, purpose, nature, and the sense that their work participates in something beyond themselves.

The deeper move

Across all twelve, the pattern is the same.

We are not fixing people. We are restoring the conditions that make perception reliable again.

When those conditions return, field awareness re-emerges naturally. Not through effort, but through alignment. Not through control, but through coherence.

And when we learn to read, hold, and honour the field in this way, change stops being something we impose.

It becomes something we participate in as observers, as contributors, and as part of a much larger unfolding intelligence.

Changing fields to create real outcomes

Fields do not change through grand redesigns. They change through local coherence.

This is one of the most counterintuitive truths for people trained in large-scale transformation. We are taught to believe that meaningful change requires comprehensive plans, structural overhauls, and organisation-wide rollouts. In reality, fields shift when small parts of the system begin behaving differently, and those differences spread.

A meeting where truth becomes speakable changes the field.

A leadership team that can share uncertainty without collapsing into control changes the field.

A product team that genuinely owns outcomes together, rather than defending roles, changes the field.

Nothing structural may have changed. No framework may have been introduced. And yet, something is unmistakably different.

That difference is coherence.

When people experience even a small pocket of coherence, where signals are not punished, where meaning is shared rather than imposed, and where responsibility is relational rather than positional, then the system begins to reorganise itself. Trust increases without mandates. Speed improves without pressure. Accountability deepens without fear. Adaptation becomes normal rather than heroic.

These micro-fields matter because fields are contagious.

Human systems learn through proximity. People carry felt experience with them. They reference it. They compare. Over time, what once felt exceptional begins to feel possible and then inevitable. This is how change actually scales: not through enforcement, but through exposure.

Working with patterns that are already present

Field-based change does not fight existing patterns. It listens for them.

Every organisation already contains patterns of behaviour, decision-making, avoidance, and flow. Some are constraining. Some are surprisingly generative. Most exist for reasons that once made sense, even if they no longer serve.

The work is not to erase these patterns, but to understand what they are protecting, what they are enabling, and where they are ready to evolve. Patterns are created by states of mind. We draw down patterns to create reality based on our current state.

Change becomes dramatically easier when we stop imposing future states and instead learn to flow with what is already present. From this stance, new patterns can be introduced gently not as instructions, but as invitations. Not as replacements, but as additions. Often new patterns become reality when old patterns become obsolete because the state of mind has changed.

Sometimes this looks like a new way of holding a conversation, or a shift in decision rhythm, or something as simple as changing who is in the room, or which question is allowed to be asked.

These are not random moves. They are informed by field awareness and a sensitivity to what the system is already reaching toward.

This is what I describe as drawing down new patterns: sensing a more coherent way of operating that already exists in potential, and giving it form inside the organisation.

Why small shifts create disproportionate effects

At this point, it is worth naming something that often remains implicit.

One reason fields feel elusive, and why small changes can have outsized impact, is that organisations do not exist in a single dimension.

Carl Sagan once explained higher dimensions using simple geometry. A three-dimensional object passing through a two-dimensional world would appear as a sequence of changing shapes. To a two-dimensional observer, this sequence would look like time. But in reality, it would simply be a projection of something more complex moving through their limited frame of perception.

Something very similar happens in organisations.

What we experience as time, delays, resistance, momentum, phases of change, is often the flattening of a multi-dimensional reality into something our linear minds can process. Patterns that exist simultaneously across identity, power, emotion, structure, and meaning are perceived sequentially. We experience them as “now this problem, then that one”, when in fact they are facets of the same underlying shape.

This idea appears in many places. David Hawkins’ Map of Consciousness describes levels not as steps, but as nested realities that collapse into behaviour. Systems thinkers hint at it when they talk about leverage points. Field practitioners experience it directly when a single insight suddenly resolves multiple seemingly unrelated issues at once.

This is why touching the field can feel almost magical.

When you shift the underlying pattern, multiple outcomes change together. What looks like speed is actually dimensional coherence; a realignment across layers from one single change.

This is also why I place a tesseract, a four-dimensional cube, at the centre of the 4D Learning and Capability Cube. The tesseract is a reminder that what we see in organisations is always a projection. Capability, learning, behaviour, and results are shadows cast by something richer moving through a higher-order space of relationships, meaning, and awareness.

We do not need to fully understand higher dimensions intellectually to work with them. We only need to accept that reality is more layered than our dashboards suggest and that fields operate across those layers simultaneously.

A bridge to what comes next

This chapter is not a manual for changing fields. That work deserves and requires its own space.

In a later chapter, we will explore in depth how to work deliberately with patterns, coherence, and field shifts to create tangible outcomes at scale. This is also a core focus of the Level 2 programme, where we move from awareness into intentional intervention: how to introduce new patterns, stabilise coherence, and support systems as they reorganise themselves.

For now, what matters is this:

Real change does not begin with redesign.

It begins with attention.

When we learn to read the field, honour what is already present, and introduce coherence where it is possible, outcomes follow naturally. Not because we forced them but because the system finally had the conditions it needed to move.

And when change accelerates without pressure, when multiple problems resolve together, when time seems to collapse and learning leaps ahead,

We are not witnessing magic.

We are seeing a deeper pattern briefly revealed before it flattens back into the familiar language of meetings, milestones, and outcomes.

Once you have seen that even once, it becomes very hard to unsee.

Courses with me:

Level 1: Organisational Change Strategy: Large scale change

Level 2: Advanced Change Strategy: Fields and coherence work

ICE-EC Cohort: Building yourself as an instrument of change

As a reader of this substack, you might be able to get a discount. DM me for details.

Subscribing

Please create a paid subscription if you want to comment on this article or support the writing of these articles. Many amazing discounts and free places on courses are often given to paid subscribers.

A subscription costs the same as buying one book per year.

Sharing and liking

I would appreciate it if you could like and share this article with your network if you think they might be interested. Please like this article if you find it valuable.

Thank you.

Love this! You have managed to draw together and articulate what is always felt and sometimes recognized, but has so far lacked a clear model and language. This is a beautiful rendering of Truth for those with ears to hear and eyes to see. I will be sharing this a hook, hoping to catch some kindred spirits ready for increased Awareness. And I very much look forward to the next chapter! Much appreciated!

Simon - You've just summed up my lifes work as a globally recognized 'expert' in all things Customer and Employee Experience with this chapter. Over the past 10 years I've worked with over 55 clients and in every case, in every way - it's the field, the vibe, the frequency that hides all of the trapped value and potential of the organization (and individuals). You are my brother from another Mother - I can't wait to see your next chapter!